SACU-EU dispute ruffles feathers

What started off as a bilateral agreement and has ended up as a multilateral dispute, coupled with a no-deal Brexit, SACU and the EU are going head to head over chicken imports.

YANNA SMITH

The European Union (EU) Commission, under the Southern African Development Community Economic Partnership Agreement (SADC EPA), has declared a dispute with the Southern African Customs Union (SACU) after the union made use of a safety valve in the agreement and imposed safeguard duties on frozen bone-in chicken portions imported into South Africa from Europe.

The safeguard duty amounts to 35.3% on the imports and was imposed on 28 September last year. This, however, follows a provisional safeguard duty of 13.9% imposed for 200 days and set up through the Trade, Development and Cooperation Agreement (TDCA) following bilateral talks between South Africa and the EU. The TDCA established preferential trade agreements between the EU and South Africa.

The South African Poultry Association (SAPA) had lodged the application “on behalf of SACU” in February 2015.

With the advent of the EPA, the TDCA’s article 16, which deals with agricultural safeguards in bilateral trade between the EU and South Africa, had effectively been repealed.

According to the EU, “the safeguard measure started under the TDCA should not have been continued under the EPA and a new investigation with a different reference period in accordance with a new legal basis should have been launched after the start of the provisional application of the EPA on 10 October 2016.”

‘Complicated history’

In the July Trade and Law Centre (Tralac) trade brief, Gerhard Erasmus writes that “the matter has a complicated history which predates the SADC EPA. It is the scene of a protracted battle by SAPA against all chicken imports, in which countries such as Brazil, are also targeted.”

Erasmus continues by saying that even though the TDCA came to an end, the matter remained on the agenda of South Africa’s International Trade Administration Commission (ITAC) and in November 2016, after EPA was provisionally applied, ITAC recommended the 13.9% safeguard duty which was officially imposed on 15 December 2016.

The measure was approved by the South African trade minister Rob Davies.

According to documents seen by Business7, following the gazetting of the new 200-day duties, interested parties were invited to provide comment.

During August, ITAC decided that there was sufficient information to indicate there was an increase in chicken imports from the EU and the SACU industry is “experiencing a threat of disturbance and/or serious injury in the market”.

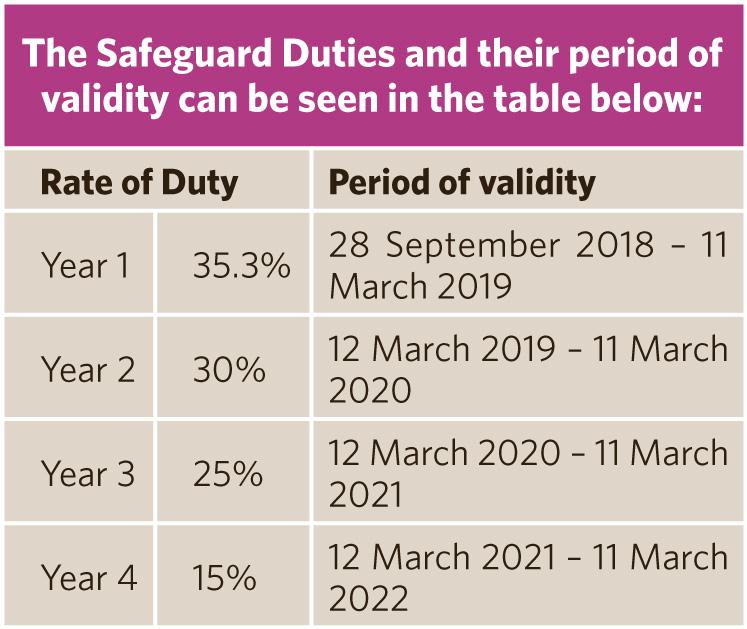

It was agreed to impose a final safeguard measure of 35.3% which would be scaled down in three phases to 0% by March 2020.

Essential facts letters were sent out in August 2017 in this regard. It received comments from interested parties and during September, ITAC told Davies that the provisions for safeguards under the bilateral TDCA (applicable to South Africa) had effectively been replaced by article 34 of the EPA (applicable to SACU and Mozambique) but added that there was no need to question the validity of its investigation as to the impact of chicken imports from the EU.

‘Sufficient info’

The commission eventually found that there was “sufficient information to justify that the matter be raised in the Trade and Development Committee” of SACU.

Under the EPA, SACU is seen as a unit, a legal entity and one that takes decisions by consensus. Moreover, the SACU Tariff Board “shall make recommendations on changes of customs, anti-dumping and safeguard duties from outside the common customs area”. The Council of Ministers shall make decisions and direct policy under SACU, with decisions taken under consensus. The Joint Council of the SADC EPA implements the tenets of the agreement and is assisted by the Trade and Development Committee.

All of these bodies are in place at SACU, save for the critical Tariff Board.

Although all the paperwork is in place and the annex has been adopted, the board never become operational.

Tariff board

Some experts question how safeguard measures could have been implemented “by SACU” without a tariff board which is tasked with this, and a well-placed source within SACU told Business7 that “South Africa refuses to discuss the matter and because all decisions must be made by consensus; our hands are tied”.

South Africa’s poultry industry is certainly buckling under the strain of Brazilian imports. SAPA’s fourth-quarter Key Market Signals in the Broiler Industry for 2018 shows that Brazilian imports made up 59.4% of all imports while the EU accounted for 18% and the US, 13.8%.

However, the EU, in its application for a formal consultation dated 14 June this year, writes that “the safeguard measure only had the effect of replacing EU imports with imports from other countries including the US and Brazil”.

According to Anton Faul of the Namibia Agricultural Trade Forum, the effect of the safeguard measures for exports from the EU to South Africa only had the effect of creating an “artificial vacuum”.

“Production takes a while to catch up and as less chicken is coming in from the EU, this gap was filled by Brazil.”

Import companies in South Africa, and the sub-region, have been doing very well.

According to Pieter van Niekerk, commercial manager at Namib Mills, meat importers seek the cheapest source of imports.

“Their businesses are built on countries who are willing to dump and they need relatively little capital to distribute their imported products as opposed to the costs of setting up an entire industrial chain.

Burden of proof

Importers want to import, thus, they will not necessarily support initiatives which protect the local industry,” he said.

Erasmus writes that the EU seeks, in its complaint, not only the burden of proof, but also how investigations should be conducted and the causality requirement of safeguard measures, among other things.

Brexit

He is of the view that the policy considerations behind this dispute do not only include SAPA regularly lobbying ITAC for support measures, as they did in November last year against Brazilian imports, but Brexit is also a consideration.

Should a no-deal Brexit take place, there will be roughly a million tonnes of poultry meat, part of the mutual trade between the EU27 and the UK, available and markets need to be sourced for this product.

Whether or not the EU wins in this dispute will have no real impact on Namibia. The country sees imports, even though there are restrictions, and in 2018, around 5 000 tonnes of chicken was in the country on the market, unaccounted for. SAPA is currently engaged in the Windhoek High Court to have import restrictions to Namibia set aside, yet they seek protection for their own industry, starting off with a bilateral agreement which was ‘transferred’ to SACU, which has no tariff board.

For Namibia’s poultry industry to grow and thrive, experts agree that two things must happen.

Firstly, the court matter, now dragging on since 2014 must be resolved to allow for closure and investment into the industry and secondly, cabinet’s March 2019 directive that all government agencies and ministries must procure locally, must be fully enforced, something that is not happening.

The European Union (EU) Commission, under the Southern African Development Community Economic Partnership Agreement (SADC EPA), has declared a dispute with the Southern African Customs Union (SACU) after the union made use of a safety valve in the agreement and imposed safeguard duties on frozen bone-in chicken portions imported into South Africa from Europe.

The safeguard duty amounts to 35.3% on the imports and was imposed on 28 September last year. This, however, follows a provisional safeguard duty of 13.9% imposed for 200 days and set up through the Trade, Development and Cooperation Agreement (TDCA) following bilateral talks between South Africa and the EU. The TDCA established preferential trade agreements between the EU and South Africa.

The South African Poultry Association (SAPA) had lodged the application “on behalf of SACU” in February 2015.

With the advent of the EPA, the TDCA’s article 16, which deals with agricultural safeguards in bilateral trade between the EU and South Africa, had effectively been repealed.

According to the EU, “the safeguard measure started under the TDCA should not have been continued under the EPA and a new investigation with a different reference period in accordance with a new legal basis should have been launched after the start of the provisional application of the EPA on 10 October 2016.”

‘Complicated history’

In the July Trade and Law Centre (Tralac) trade brief, Gerhard Erasmus writes that “the matter has a complicated history which predates the SADC EPA. It is the scene of a protracted battle by SAPA against all chicken imports, in which countries such as Brazil, are also targeted.”

Erasmus continues by saying that even though the TDCA came to an end, the matter remained on the agenda of South Africa’s International Trade Administration Commission (ITAC) and in November 2016, after EPA was provisionally applied, ITAC recommended the 13.9% safeguard duty which was officially imposed on 15 December 2016.

The measure was approved by the South African trade minister Rob Davies.

According to documents seen by Business7, following the gazetting of the new 200-day duties, interested parties were invited to provide comment.

During August, ITAC decided that there was sufficient information to indicate there was an increase in chicken imports from the EU and the SACU industry is “experiencing a threat of disturbance and/or serious injury in the market”.

It was agreed to impose a final safeguard measure of 35.3% which would be scaled down in three phases to 0% by March 2020.

Essential facts letters were sent out in August 2017 in this regard. It received comments from interested parties and during September, ITAC told Davies that the provisions for safeguards under the bilateral TDCA (applicable to South Africa) had effectively been replaced by article 34 of the EPA (applicable to SACU and Mozambique) but added that there was no need to question the validity of its investigation as to the impact of chicken imports from the EU.

‘Sufficient info’

The commission eventually found that there was “sufficient information to justify that the matter be raised in the Trade and Development Committee” of SACU.

Under the EPA, SACU is seen as a unit, a legal entity and one that takes decisions by consensus. Moreover, the SACU Tariff Board “shall make recommendations on changes of customs, anti-dumping and safeguard duties from outside the common customs area”. The Council of Ministers shall make decisions and direct policy under SACU, with decisions taken under consensus. The Joint Council of the SADC EPA implements the tenets of the agreement and is assisted by the Trade and Development Committee.

All of these bodies are in place at SACU, save for the critical Tariff Board.

Although all the paperwork is in place and the annex has been adopted, the board never become operational.

Tariff board

Some experts question how safeguard measures could have been implemented “by SACU” without a tariff board which is tasked with this, and a well-placed source within SACU told Business7 that “South Africa refuses to discuss the matter and because all decisions must be made by consensus; our hands are tied”.

South Africa’s poultry industry is certainly buckling under the strain of Brazilian imports. SAPA’s fourth-quarter Key Market Signals in the Broiler Industry for 2018 shows that Brazilian imports made up 59.4% of all imports while the EU accounted for 18% and the US, 13.8%.

However, the EU, in its application for a formal consultation dated 14 June this year, writes that “the safeguard measure only had the effect of replacing EU imports with imports from other countries including the US and Brazil”.

According to Anton Faul of the Namibia Agricultural Trade Forum, the effect of the safeguard measures for exports from the EU to South Africa only had the effect of creating an “artificial vacuum”.

“Production takes a while to catch up and as less chicken is coming in from the EU, this gap was filled by Brazil.”

Import companies in South Africa, and the sub-region, have been doing very well.

According to Pieter van Niekerk, commercial manager at Namib Mills, meat importers seek the cheapest source of imports.

“Their businesses are built on countries who are willing to dump and they need relatively little capital to distribute their imported products as opposed to the costs of setting up an entire industrial chain.

Burden of proof

Importers want to import, thus, they will not necessarily support initiatives which protect the local industry,” he said.

Erasmus writes that the EU seeks, in its complaint, not only the burden of proof, but also how investigations should be conducted and the causality requirement of safeguard measures, among other things.

Brexit

He is of the view that the policy considerations behind this dispute do not only include SAPA regularly lobbying ITAC for support measures, as they did in November last year against Brazilian imports, but Brexit is also a consideration.

Should a no-deal Brexit take place, there will be roughly a million tonnes of poultry meat, part of the mutual trade between the EU27 and the UK, available and markets need to be sourced for this product.

Whether or not the EU wins in this dispute will have no real impact on Namibia. The country sees imports, even though there are restrictions, and in 2018, around 5 000 tonnes of chicken was in the country on the market, unaccounted for. SAPA is currently engaged in the Windhoek High Court to have import restrictions to Namibia set aside, yet they seek protection for their own industry, starting off with a bilateral agreement which was ‘transferred’ to SACU, which has no tariff board.

For Namibia’s poultry industry to grow and thrive, experts agree that two things must happen.

Firstly, the court matter, now dragging on since 2014 must be resolved to allow for closure and investment into the industry and secondly, cabinet’s March 2019 directive that all government agencies and ministries must procure locally, must be fully enforced, something that is not happening.

Comments

Namibian Sun

No comments have been left on this article