Push to honour genocide heroes

Ovaherero historian Festus Muundjua has made a call for the dignified unveiling of human remains at Shark Island.

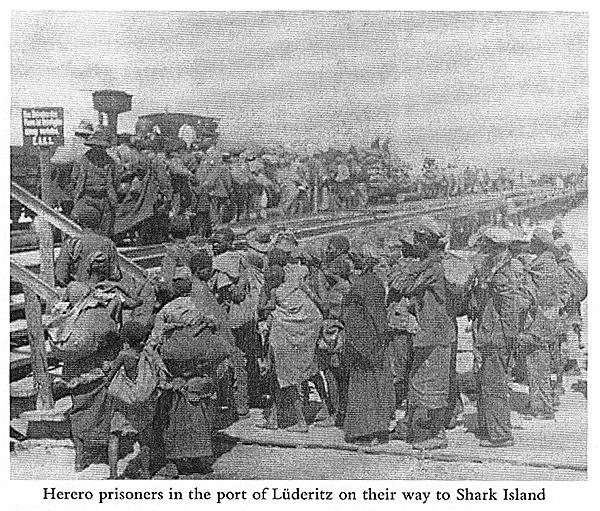

Culture minister Katrina Hanse-Himarwa has called for a national debate on how to honour the fallen heroes of the German genocide, in particular those who perished at or en route to the Shark Island concentration camp.

Hanse-Himarwa responded to a call from local historian Festus Muundjua, who urged the minister to arrange for a “solemn, respectful and dignified” unveiling of human remains at Shark Island and its surrounding areas.

“Basically, wherever people have fallen during the genocide years is a national issue. This requires a national debate and consensus on how we are going to honour them. Honouring those people is not negotiable; it is something that must be done,” Hanse-Himarwa said.

Muundjua referred in particular to the narrative that it cost one Ovaherero life to construct 100 metres of the Lüderitz railway line.

“If you have travelled from Keetmanshoop to Lüderitz and have seen the terrain of the Namib Desert in hot summers and freezing winters, imagine the Ovaherero people that worked there, carrying those heavy steel rails on their shoulders for hours on end, while enduring thirst and hunger, and with a ruthless German soldier, sjambok in hand, behind you,” said Muundjua.

He added the remains of these labourers too must be treated with dignity, just like the skulls in Germany.

“Many of our people died on the way and were buried under the sand dunes or in shallow graves. Some of their bones were collected by Ida Hoffmann and I think she buried them already,” he said.

Muundjua believes more awareness must be raised and Namibian youth must be taught about the realities of the 1904-08 genocide.

He highlighted Swakopmund as a focal point of that dark era, emphasising the terrible history of genocide began there.

“All the colonial agents such as missionaries, traders, lebensraum seekers, scientists, geologists, hydrologists, mineralogists, hunters, exterminators, camels, horses, drums of poison for poisoning water points, etc. disembarked at Swakopmund,” he said.

According to Muundjua, the Nama and Ovaherero who were taken to Cameroon and Togo, and the skulls taken to Germany, were shipped from Swakopmund.

“What used to be the biggest concentration camp, now a graveyard with some of the headless bodies that lie beneath the soil, is in Swakopmund. The street where our people were being killed is still there; and not far away from that the very church where the fresh heads of our people were boiled, cleaned and then packed in boxes to be shipped to Germany, is still there in Swakopmund.”

Although he feels there are hypocrites among present-day Germans, Muundjua is hopeful that one good day there will be a genuine paradigm shift on the part of German politicians, who do not want to come to terms with what their forebears did to the Nama and Ovaherero.

JEMIMA BEUKES

Hanse-Himarwa responded to a call from local historian Festus Muundjua, who urged the minister to arrange for a “solemn, respectful and dignified” unveiling of human remains at Shark Island and its surrounding areas.

“Basically, wherever people have fallen during the genocide years is a national issue. This requires a national debate and consensus on how we are going to honour them. Honouring those people is not negotiable; it is something that must be done,” Hanse-Himarwa said.

Muundjua referred in particular to the narrative that it cost one Ovaherero life to construct 100 metres of the Lüderitz railway line.

“If you have travelled from Keetmanshoop to Lüderitz and have seen the terrain of the Namib Desert in hot summers and freezing winters, imagine the Ovaherero people that worked there, carrying those heavy steel rails on their shoulders for hours on end, while enduring thirst and hunger, and with a ruthless German soldier, sjambok in hand, behind you,” said Muundjua.

He added the remains of these labourers too must be treated with dignity, just like the skulls in Germany.

“Many of our people died on the way and were buried under the sand dunes or in shallow graves. Some of their bones were collected by Ida Hoffmann and I think she buried them already,” he said.

Muundjua believes more awareness must be raised and Namibian youth must be taught about the realities of the 1904-08 genocide.

He highlighted Swakopmund as a focal point of that dark era, emphasising the terrible history of genocide began there.

“All the colonial agents such as missionaries, traders, lebensraum seekers, scientists, geologists, hydrologists, mineralogists, hunters, exterminators, camels, horses, drums of poison for poisoning water points, etc. disembarked at Swakopmund,” he said.

According to Muundjua, the Nama and Ovaherero who were taken to Cameroon and Togo, and the skulls taken to Germany, were shipped from Swakopmund.

“What used to be the biggest concentration camp, now a graveyard with some of the headless bodies that lie beneath the soil, is in Swakopmund. The street where our people were being killed is still there; and not far away from that the very church where the fresh heads of our people were boiled, cleaned and then packed in boxes to be shipped to Germany, is still there in Swakopmund.”

Although he feels there are hypocrites among present-day Germans, Muundjua is hopeful that one good day there will be a genuine paradigm shift on the part of German politicians, who do not want to come to terms with what their forebears did to the Nama and Ovaherero.

JEMIMA BEUKES

Comments

Namibian Sun

No comments have been left on this article